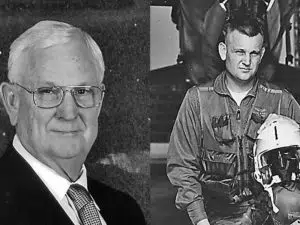

Alton B. “Al” Meyer, Vietnam War veteran

Alton B. “Al” Meyer, Vietnam War veteran

In late February and early March of 1973, I, along with millions of other Americans, watched our televisions with tears in our eyes, as our American POWs returned home from North Vietnam. Some could hardly walk while others could only walk with assistance. Being able to witness those reunions with their wives and children was heartwarming to all of us. One of the reunions we witnessed was between Al Meyer, his wife Bobbie and their children.

Life for Al Meyer began in rural Gillespie County on January 2, 1939. According to Meyer, “I was born into a farming family and I attended Cherry Mountain School until the fifth grade when it consolidated with the Fredericksburg schools. I graduated from Fredericksburg High in 1956 and enrolled at A&M. I was in the Corps of Cadets and received a commission in the Air Force upon my graduation in 1960. I started my training as a navigator at James Conley Air Base in Waco. My wife Bobbie and I were married in October 1960 and I continued my training with the Air Force.

“I was stationed at various bases for training and duty stations, ending up in Duluth, Minnesota. The first day there the temperature was thirty degrees below zero and the car wouldn’t start.” They knew they weren’t in Texas anymore. “Finally in October 1966, I received orders to report to Dulles Air Force Base outside Las Vegas, Nevada, to be a part of what was called “Project Wild Weasel.” I didn’t know what it was all about, but apparently they needed people real quick because our training program which usually took four to five months lasted three weeks. We were shown how the equipment worked and how the ejection seat worked. The equipment was state-of-the-art in electronics. What was 10,000 pounds of equipment in a B-52 was now located in a little box on the panel in my plane, which was a F-105. We were shipped to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines for our jungle survival training. In our training, we worked with the ‘Negritos,’ people who were aboriginal natives to the area and who had been our ally since World War II.

“From there I was assigned to the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing and the 333rd Tactical Fighter Squadron. We were located at Takli Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand. My first combat mission occurred in January 1967. For that mission, we arrived at our plane around 4 a.m. I was so inexperienced with the plane and the equipment that I had to have one of the ground crew show me where the cockpit light switch was located.

“Our targets were always in North Vietnam. All we knew about the targets were the coordinates. If we didn’t drop all of our bombs we would contact our command post located in Laos for secondary targets. Most of the time we were sent to secondary targets bombing NVA truck traffic moving down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was located just inside the border in Laos from South Vietnam.

“Our target areas were divided in to six route pacs. Route pacs one through four were easier targets while pack five was near Dien Bien Phu. The hardest targets were those located in Route Pac Six. That area was the Red River Valley, Hanoi and Haiphong Harbor. It is hard to describe the defenses the NVA had set up in this area. When we flew over, the ground would sparkle from their gun muzzle flashes. Then, there were the SAMS (surface to air missiles). Most planes were shot down by the flak but the SAMS were our planes’ greatest danger. If a SAM was launched, we would fire our ‘Shrike’ missiles, which would lock onto the radar site that was operating the SAM. When we fired the ‘Shrike,’ which could be fired from 20 miles away, the NVA would turn their radar off to avoid being hit by our ‘Shrike.’ This made the SAM they had launched totally ineffective. Some of the pilots reported that when they dropped their cluster bombs, they sometimes could see the SAM coming up at them from the launch site.

“My last mission occurred on April 26, 1967. Prior to that date, I had flown 35 missions, seven to Route Pac Six, the other 28 to other pacs. On that date, I slept late because I wasn’t on a flight schedule. I was on my way to the officers club for breakfast when someone told me to report to headquarters because I was now on the flight schedule. That also caused me to miss lunch.” Meyer would not enjoy another American meal for almost seven years.

“I was a fill-in on that mission that was being made up by using some planes coming out of maintenance. I remember it was cloudy that day and we were flying at 18,000 feet to stay above the cloud cover. Those were almost suicidal conditions in North Vietnam because when a SAM gets to that height, they are moving at about mach four speed and there is not much you can do. As we flew above the clouds, a missile came out of the clouds below us and detonated just above us. That put a lot of holes in my canopy and our plane. There was so much fire and smoke that I couldn’t see the instrument panel. I guess I pulled the ejection lever but I don’t remember doing it. The fire and smoke is the last thing I remember.”

Part two

On April 26, 1967, Al Meyer was on his 36th mission over North Vietnam. They were flying above cloud cover, which is a very dangerous thing to do, when his plane was hit by a surface to air missile. Meyer remembered the fire and smoke in his cockpit but does not remember pulling his ejection lever. His next memory was of waking up in a bamboo hut filled with screaming North Vietnamese.

As related by Meyer, “I awoke to a bunch of screaming Vietnamese and a terrible pain my leg. I remember that I was laying on a stretcher of some kind. My skin was burned and what wasn’t burned was bruised. I knew this because I was completely nude. I remember them taking me outside the hut for a village kind of pep rally. One soldier asked me if I was a Soviet because Soviet pilots were flying the North Vietnamese MIGs. I remember telling him no. He gave me a pack of cigarettes and I knew from the packaging on the cigarettes that I was in North Vietnam.

“Later that night soldiers came to pick me up. The soldiers carried me on a stretcher for a long way. It was night, it was cold, it was rainy, I was naked and my leg hurt terribly. They finally came to where a vehicle was parked waiting for us. On the trip I would pass out, wake up and then pass out again. I was placed in a Jeep-type of truck with my broken leg sticking out the back of the truck. When we came to a village, the driver would stop, get on the hood of the truck and with a bull horn, whip up the crowd. The villagers would hit me and some would twist my broken leg. The meanest were the old women with the beetle nut-stained teeth. Sometimes the guards would have to use the butts of their rifles to get them to back off. I saw them stab one villager with a bayonet. This activity was repeated in every village we came to.

“I finally arrived at a hospital of some sort. The doctor there was Caucasian, I think he was Swedish but was a Communist. He placed a cast on me from my chest to my foot. Now I was in a cast in the back of that same truck banging up and down a rough road. It was just as painful on my leg as before. I continued to lose consciousness, regain it, lose again until I began to hallucinate.

“It took us two days to travel the 40 to 50 miles we were from Hanoi. The roads there were terrible. When we arrived, they delivered me to an interrogation room on my stretcher. I wouldn’t talk to the interrogator so he left. When he left, the trap door opened enough for a voice to ask in English, ‘Are there any peace negotiations on POW exchange going on?’ I didn’t answer. I would later learn that voice was that of Robbie Reisner, our senior prisoner of war. We all knew who he was. When the American sounding voice asked again, I said ‘No.’ He said, ‘We are praying for you,’ and left.

“The interrogator came back and told me that if I didn’t talk to them, they were going to withhold medical treatment and I would die. I didn’t say anything. They tied my wrists and elbows together behind my back and raised them with a rope from the ceiling until my elbows that were tied behind my back were higher off the floor than my head. The pain was so bad I passed out. When I came to, I told them I would talk. When they asked for certain information I would tell them something that was not correct. I made up targets and missions. He knew I was lying and then told me some things about our operations that were true. The interrogators told me he had talked to my pilot, Major Dudash. I don’t know if he ever did, because he never showed up in Hanoi. In 1983, his remains were sent home.

“I was placed in what the POWs called Heartbreak Hotel. I was placed in this dungeon type place that had two concrete bunks. I laid on the floor in the stretcher for a week. One night they carried me to an interrogator’s room, and they brought in another American, a 105 pilot named John Dramesi. They told us we would be roommates. John had been shot down four weeks before me. They moved us into a cell in a building that contained three other cells. The 105 pilots had trained in Las Vegas and they called these buildings “Little Vegas.” I was in the Golden Nugget. When they carried me outside on my stretcher, I was blindfolded and taken to a hospital. I was received X-ray and had surgery on my leg by the same Swedish doctor and another doctor I think was Russian. The next day they took me back to my cell and I was then moved to another camp across town to what would become known around the world as the ‘Hanoi Hilton.’

Part three

Al Meyer was held as a POW in North Vietnam from April 26, 1967 until Sunday March 4, 1973. It was five years, 11 months and 10 days gone from his life and time spent with his family. Some POWs suffered and died while others gathered strength and resolve. Al Meyer is one of the later.

Meyer had suffered a broken leg when shot down which was operated on. He was returned to prison the day after the operation. According to Meyer, “The leg became infected and swelled to twice its normal size. Finally, a Vietnamese medic cut the incision open so it would drain. They gave me some medicine but my leg drained for about six months. When the cool weather came in October, it finally healed. I had been on my back on that stretcher for three months.

“We had one guy in our group who was 42 years old, the rest of four of us were 29. He made me sit up until I passed out. Then he made me do it again until I could stand without passing out. Then it was being able to walk again. During this time I had not been able to bathe, which could only be done by walking outside to a trough and pouring water over your head and bathing that way. That was such a relief to be able to bathe which we did every day, except Sunday. That is how we know it was Sunday.

“We were isolated from the other guys in the other cells and we were not allowed to communicate with each other. Prior to my arriving, the group had developed a code for communication. The code was the alphabet with the letter K eliminated. The alphabet was arranged in a grid with five rows of letters in five columns. The first tap on the wall of the cell would indicate the row and the second set of taps would indicate the column. In place of the letter K that was eliminated, we used the letter C. If we were caught communicating, you would be severely beaten. Therefore, one cough would indicate danger and two coughs, all clear.

“The food was usually a watery soup of some kind with some moldy bread occasionally. You had to be careful with the bread, because the mold could make you very sick. In the winter the soup would be cabbage or a type of turnip soup. We were moved to another camp which had been an old movie studio. In this camp we had nine guys to a room and in this group was John Draminsi who had been my first roommate. One night John and another guy were able to escape by us lifting them to the roof where they worked a hole in the roof and escaped. Two hours later they were captured. That was when all hell broke loose. All of us in that cell were placed in a solitary confinement and then one at a time tortured until all answers agreed. They did the same to the guys in the other cells who didn’t know a thing about the escape. The guy who escaped with John was killed but John managed to survive the torture and the long time he spent in solitary confinement.

“The summer of 1969 was the worst time. It was so hot. The windows had been bricked so there was no air, we just sat and sweated. Things began to get better in September of 1969 when Ho Chi Minh died. Overnight, the treatment improved. There were no more beatings or torture interrogations. In September of 1970, we were placed in an open-air camp with large cells. It was sort of like the ‘Hogan’s Heros’ type camp. Then in November 1970 all hell broke loose again when the U.S. attempted the Son Tay Raid with American forces. The camp they hit which was a few miles away was empty of U.S. POWs. That was when we were moved to the Hoa Lo prison near the Chinese border. It was without electricity, it was cold and dark, but because of the rats, we also had plenty of cobra and krate snakes, some of the most poisonous snakes in the world.”

Meyer’s story originally ran in The Eagle in December 2012.

If you know a World War II, Korean, or Vietnam War veteran whose story should be told, contact the Brazos Valley Veterans Memorial at www.bvvm.org or Bill Youngkin at 979-776-1325.